Making sense of our connected world

The Virtual Judge. On the Butterfly-Effect of Internet-enabled Judicial Review

In July this year, I had the privilege to hold a lecture at the Brazilian Institute for Public Law and Public Administration (IDP). Although the topic was an analysis of the regional impact of Marco Civil da Internet, it gave me the opportunity to have a closer look to fascinating developments in the digital modernization of the State, which confirm that we (me included) too often tend to discount the efforts in the global south as lagging behind Europe or the US. In doing so, we neglect the profound institutional and legal changes that Internet–enabled innovations can trigger within our public administration. We, at the research group on the Digital Public Administration, are interested not only in the adoption of internet-based technology by the public sector, but in the legal, institutional and organizational transformation of the administrative state.

One fascinating case of digital transformation is what I call the “the virtual judge” because it owes its transformative impulse not to an enabling law (like the German e-Government law), or a distinctive top-down policy (like the American cloud-first policy), but to the vision of higher public officials, who decided to use their leeway to re-shape the administration of justice. In doing so, they not only produced an unprecedented wave of optimization and transparency in the Brazilian judiciary, but also materially influenced the highly formalized interpretation of constitutional law.

Here is the story: The Brazilian judicial system has a Constitutional Court, the “Supremo Tribunal Federal”, established in 1890 and consequently ratified by the constitutions that followed. Among other constitutional attributions, the Court has the power to review the rulings from lower courts through a distinctive judicial remedy called Recurso Extraordinario, which aims at assuring “the positive integrity; validity, the authority and uniformity of the interpretation of the Constitution”. This procedure was established by the Constitution of 1891 and found inspiration in U.S. law. Administratively, the parties file this remedy before the same inferior court that issued the contested judgement; and the latter conveys the file to the Constitutional Court.

The rapid growth of cases that reached the Court, made it increasingly difficult to deal with them timely. During the 20th century, the Court repeatedly tried to restrict the requirements of admissibility. From 1975 onwards, the Court introduced the term “claim of relevance” (arguição de relevância), with the explicit goal to filter the workload. However, because the Court decided the question of relevance in small, private council sessions and behind closed door, the initiative encountered massive criticism because of its lack of transparency and legitimacy. The Court was pushed to increasingly hand down functionally-defensive rulings (jurisprudência defensiva), where formalistic quarrels dominated over the higher task of harmonizing the interpretation of the Constitution; and yet, there was no way to handle the growing backlog.

In 2004, a constitutional amendment introduced an explicit requirement for the Constitutional Court to admit the judicial remedy. It required that for the matters to be reviewed by the Court, the core legal issue had to bear general repercussions (repercussão geral). If the case does not have the potential for general (constitutional) repercussions, the case is not admitted for review. The overall goal of the amendment was to alleviate the Court’s case load and bolster the multiplicative effects of its rulings.

The proceeding for establishing whether a judicial quarrel has or not the required “general repercussions” is a novelty for the Brazilian –and many South American– judicial administration. In addition, the Court’s internal ordinance (regimento interno) introduced in 2006 the possibility of optimizing procedures like this with the help of “electronic means”.

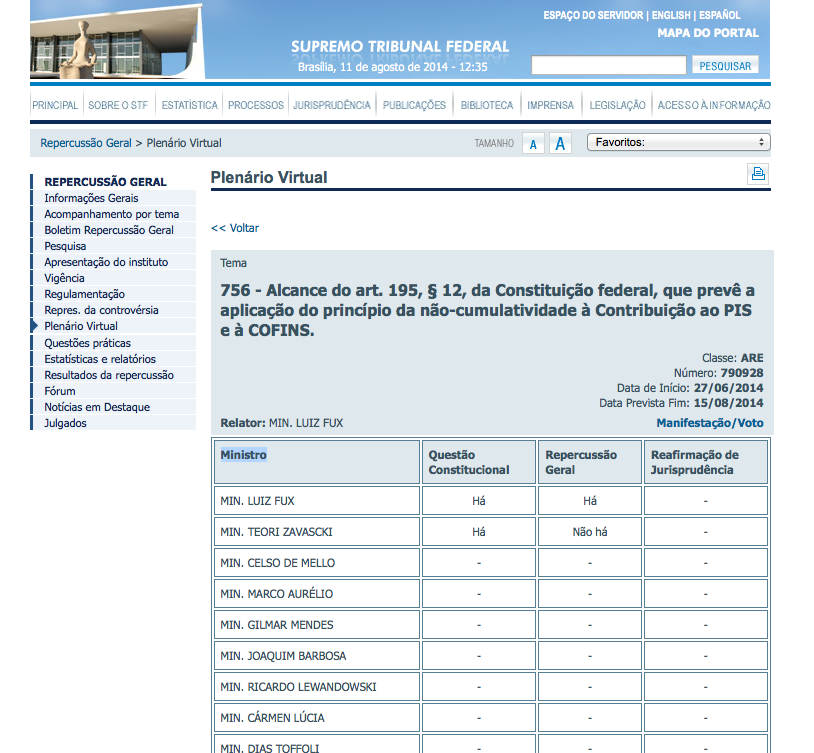

The Constitutional Court used this administrative window of opportunity to reorganize its work and introduced the “virtual plenaries”, an online platform that allows for a legal debate among the judges of the Court with written statements. Most importantly, the online platform includes a voting app that tracks the opinions and votes of each single judge in regard to the issue of whether the case at stake has or not the required “general repercussions” for being admitted to review. Instead of deliberating in a formal hearing, the judges can view the main opinions of their peers and the statements of the litigating lawyers, and cast a vote within 20 days counted from the moment the case was posted on the Court’s web site.

The spectacularity of this new procedure, is that the voting record can be followed in real time during the twenty days as the judged cast their vote in the moment they see suit. Additionally, the Court has rearranged the formats of the lawsuits, compelling the parties and the inferior courts to adapt their reports so as to suit the file descriptors of the online platform. When cases arrive at the Court, it is expected that they contain the new coding, an executive summary, as well as a suitable snippet that makes the online search on the website more user friendly.

Fig. 1: The Virtual Plenary voting mask.

Up to this point, the plan worked on paper. In order to make these change work in practice, the Court had to engage in a dialogue with the subordinate judges, and socialize the benefits of the new electronic means. Lower courts were used to submitting the court files without scrutinizing whether the plaintiffs had complied with all formal requirements in their scripts. Now, as the “virtual plenaries” are accessible through the Internet, lower judges must adapt to the internal search functions of the platform, and summarize most of the information before it reaches the Constitutional Court. Of course, much of this socialization has spilled over to litigators, who have also adapted their written presentations to fit the online mask of the plenary. The gain in efficiency has been so spectacular that the Court has reduced its backlog from 10 000 cases, to less than 2 000 cases; and the number is progressively diminishing. This has allowed the Court to oversee the content and relevance of the cases, underpinning the effort to become a court that is able to accurately select its cases in order to produce judicial precedents. A shift, I am told by local observers, that aims at bringing the Court nearer to the style of the German Constitutional Court.

In addition, the Brazilian judiciary began broadcasting important hearings on Youtube. This has led to interesting developments in the legal profession. Watching TV or Youtube streaming is becoming an inherent part of the work routine in specialized law firms; instead of large libraries, they are opting for comfortable couches in multimedia rooms. Some practitioners told me, that their colleagues are developing impressive performativity skills as they now also face an enlarged audience through the webcast sessions.

In sum: Internet produces marked transformation within the public administration. And yet, the analyst usually assumes that organizational change and legal transformation follows a kind of master plan (like an e-Government law or strategy). If we look carefully, however, we will see important transformations within our public administration that begin with a subtle improvement by, for instance, a visionary judge followed by a butterfly-effect that can change even the interpretation of constitutional law. The story of the virtual plenaries should encourage us to complement dominating analytical perspectives on e-Government that focus on big strategies or general laws with cases of functional public innovation at the micro-level. The Digital Public Administration we are looking for might present itself in charming stories like that of the Brazilian “virtual judge”.

Words of gratitude: I would like to thank Min. Gilmar Mendes judge at the Supremo Tribunal Federal, and his professional staff, especially Luciano Fuck, Marco Reis Magalhães and Sergio Ferreira Victor for helping me understand the Virtual Plenaries. All errors remain mine.

Recommended literature (in Portuguese):

- Fuck, Luciano (2010) O Supremo Tribunal Federal e a repercussão geral. Revista de Processo, v. 35, No. 181

- Mendes F. Gilmar and Branco G. Paulo (2014) Curso de Direito Constitucional. Saraiva: São Paulo, 9th ed. p. 1102

Pictures:

- Butterfly in flight by Dwight Sipler

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Research issues in focus

Escaping the digitalisation backlog: data governance puts cities and municipalities in the digital fast lane

The Data Governance Guide empowers cities to develop data-driven services that serve citizens effectively.

Online echoes: the Tagesschau in Einfacher Sprache

How is the Tagesschau in Einfacher Sprache perceived? This analysis of Reddit comments reveals how the new simplified format news is discussed online.

Opportunities to combat loneliness: How care facilities are connecting neighborhoods

Can digital tools help combat loneliness in old age? Care facilities are rethinking their role as inclusive, connected places in the community.