The Consent Fallacy

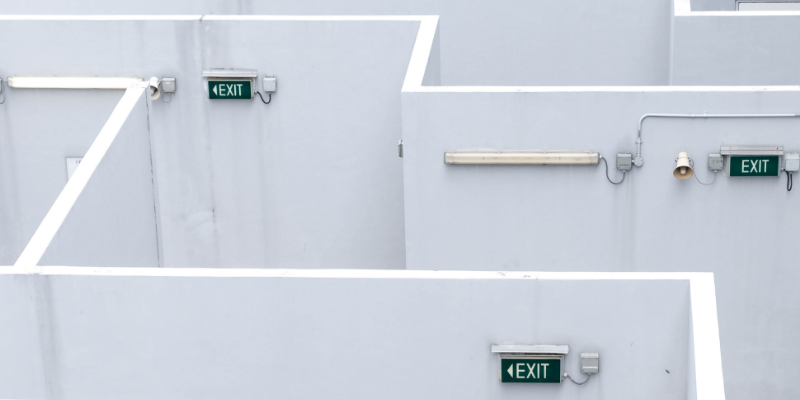

Humans are not the rational cost-benefit analysis machines that law and economy often wants them to be. Still, when fundamental rights like self-determination are at stake, it is up to you to make the right choices. Our brains are fallible and there is no legal safety net. Do we need better protection? Are legislators asking too much by relying on our consent?

Introduction

The often cited Privacy Paradox describes how people happily share – even sensitive – data despite great concerns for their privacy. But how paradoxical is this behaviour really? Existing European legislation on the processing of personal data builds its steadfast barrier against exploitation and harm on the consent of the individual. However, depending on the level of potential risk involved, letting citizens decide for their own good is not necessarily the norm in other areas of life. Drugs are subject to prohibitions and age restrictions, poisonous food ingredients and pesticides are banned, and it is not up to your mood whether you would like to wear a seat belt. Can consumers carry the burden of choice? Or did we in the protection of human rights fall prey to a consent fallacy?

Attention, economy!

Meet the ad-based business model. The attention economy offers ‘free’ digital services in exchange for cognitive real estate. Only when we pay attention to ads – or better even click on them – advertisers get a return on their investment. For that reason, platforms are incentivised to optimise their platforms for user engagement – and to collect and provide detailed metrics on user behaviour to their customers. These clusters of data range from people living in a certain area, over having a certain hobby, to even having similar, deeply rooted fears. It is no secret, and users consent to these conditions – usually, without fully grasping the trade-off.

The ultimate euphemism

Engagement orientation sounds great at first glance. It implies relevant and entertaining content, personalised to your taste. But what makes us engage? Essentially, it boils down to what attention actually is and why we pay it to what. Attention as a capacity for selective information processing as well as ‚presence of mind‘ (Franck, 2019) in its core is an evolution-driven mechanism to preserve our precious energy levels. Besides and because of that, it is a deeply rooted survival feature to make us focus on threats (Davenport & Beck, 2001): those who unswervingly admired the flower in front of them while a lion approached its easy dinner ultimately did not pass on their genes. So, what grabs our attention the most is likely fear-inducing, extreme, new, threatening, or loud. Carefully think through how this may influence online content.

Feel free to inform yourself

You might ask yourself: Why aren’t we legally protected against such practices? We as users choose not to be – some of us every single day anew. Consent, in the sense of EU data protection laws, shall be informed and voluntary. Presumably, we are being informed by multiple page long privacy statements before we use a digital service. But this systematic information overload does not inform us in the true meaning of the norm, providing a false sense of justification (Poursabzi-Sangdeh et al., 2021). The term ‘cookie’ presents a wonderful metaphor for an action you cannot resist despite being somewhat aware of its potentially negative consequences. How voluntary do we consent to the processing of our data in light of our brain’s ‘energy-efficient’ state when we mindlessly scroll through engagement-driven feeds? Digital service providers ubiquitously utilise dark design patterns (Weinzierl, 2020) like colour contrasts and persuasive language (Martini, 2022; Ruschemeier, 2020), making an effort to trick our lazy brains into choosing the easy opt-i(o)n.

Consent without consensus

Despite all of this, being able to freely and independently arrange one’s private legal relationships sounds fair – and is essentially what German law means with its constitutionally protected ‚informational self-determination‘ (Rüthers & Stadler, 2014). Is it fair though? For proper consent-giving, the GDPR demands the absence of clear imbalances in the parties’ power relationship (Stemmer, 2022). In a society that is socially and professionally to a large extent dependent on social networks, doubts might be raised. No law states that you have to have a bank account, but to participate in modern society, you are forced to have one. Social factors like the fear of missing out (Wildt, 2015), rooted in a deep desire for belonging to social groups, leading to conformity, do not seem to be part of the legislators’ consideration. Also, social media addiction is no recent discovery (Alter, 2017; Fogg, 2003). Just search for ‚intermittent variable reinforcement‘ and reflect whether this effect feels eerily resounding to you in the context of your daily platform usage. The crux of an addiction – no matter how severe – lies in involuntary behaviours, regardless of being informed on risks.

The burden of choice

No decision is free from external influences. However, certainly not many decisions are as highly influenced by not only profit-oriented actors but just as well our very own fallible nature as the decision to use or not use platforms and accept or decline cookies. Legislators should ask themselves whether an almost conditioned click-response to service-interrupting pop-ups really represents the bulletproof protection of fundamental rights they claim it to be. Art. 8 II 1 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights through the GDPR – which is unable to counter the incentive structure of the ad-based business model – manifested in a behavioural market failure. To end this “race to the bottom of the brain stem“, it requires a paradigm shift in EU legislation (Weinzierl, 2020), turning away from the homo oeconomicus towards a more humane – and realistic – homo empathicus.

References

Alter, A. (2017). Irresistible – The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked. Penguin Press, New York.

Davenport, T. H., and Beck, J. C. (2001). The Attention Economy. Harvard School Press, Boston.

Fogg, B. J. (2003). Persuasive Technology – Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, San Francisco.

Frank, G. (2019). Ökonomie der Aufmerksamkeit. 12th ed., Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich.

Martini, M. (2022). Art. 25 GDPR, Rn. 46a in Eds. Wolff, A., and Brink, S., BeckOK Datenschutzrecht, 40th ed., C. H. Beck Verlag, Munich.

Poursabzi-Sangdeh, F. et al. (2021). Manipulating and Measuring Model Interpretability. Cornell University, arXiv:1802.07810v5 [cs:ai].

Ruschemeier, H. (2020). 9. Speyerer Forum zur digitalen Lebenswelt: Regulierung Künstlicher Intelligenz in der Europäischen Union zwischen Recht und Ethik. NVwZ 2020, p. 447.

Rüthers, B., and Stadler, A. (2014). Allgemeiner Teil des BGB. 18th ed., C. H. Beck Verlag, Munich.

Stemmer, B. (2022). Art. 7 GDPR in Eds. Wolff, A., and Brink, S., BeckOK Datenschutzrecht, 40th ed., C. H. Beck Verlag, Munich.

Weinzierl, Q. (2020). Dark Patterns als Herausforderung des Rechts. NVwZ 2020, p. 1087.

Wildt, B. T. (2015). Digital Junkies – Internetabhängigkeit und ihre Folgen für uns und unsere Kinder. Droemer Verlag, Munich.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Data governance

Online echoes: the Tagesschau in Einfacher Sprache

How is the Tagesschau in Einfacher Sprache perceived? This analysis of Reddit comments reveals how the new simplified format news is discussed online.

Opportunities to combat loneliness: How care facilities are connecting neighborhoods

Can digital tools help combat loneliness in old age? Care facilities are rethinking their role as inclusive, connected places in the community.

Unwillingly naked: How deepfake pornography intensifies sexualised violence against women

Deepfake pornography uses AI to create fake nude images without consent, primarily targeting women. Learn how it amplifies inequality and what must change.