Making sense of our connected world

Towards a socially just gig economy in Kenya: Stakeholder engagement and regulatory processes

Digital platforms are fundamentally changing the world of work. At the click of a button, we can order food or services online to our doorstep in the so-called gig economy. While the platform economy opens immense opportunities for flexible, gainful and convenient entrepreneurship, the precarious livelihoods of workers and service providers often remain unaddressed. In particular, workers from economically developing countries are often subject to repetitive gig work, low levels of job security and high exploitation risks. As part of the SET project, Kutoma J. Wakunuma and Tom Kwanya have studied the livelihood of workers in the gig economy of Kenya, which allows us to better understand the perks and perils of the gig workers in the Global South.

Kenya’s gig economy: a convenient and cost-effective work?

About five years ago, getting a taxi in Kenya meant either standing on the roadside and waving one down or wandering around the town centre looking for taxi bays. Similarly, food delivery was limited to hotel residents who could request room service. Everyone else had to pop into a restaurant and order takeaway. Today, virtually all such basic services are available at the click of a button on digital platforms. Behind these platforms are thousands of people who deliver the services to clients conveniently and cost-effectively. Besides bringing services closest to the clients, these platforms also open immense opportunities for flexible, gainful and convenient entrepreneurship.

Kenya’s 1 million gig workforce

A 2019-report by Mercy Corps put the number of online gig workers in Kenya at 36,500. However, there is evidence that the gig economy model in Kenya makes it difficult to count many online gig workers. For instance, most online gig work accounts have been set up by individuals who employ several others to deliver the services. Similarly, some online gig workers deliberately hide their identity for legal and tax reasons. Therefore, stakeholders place the realistic number of gig workers in Kenya at about 1 million*. The stakeholders, including policymakers, civil society members, donors and platform owners also emphasised that the number of online gig workers in the country is growing exponentially. Indeed, the Federation of Kenya Employers (FKE) projects has projected that in the not-so-distant future, more workers in Kenya will perform multiple types of online and offline gig work with varying levels of formality and high levels of flexibility rather than rigid, formal employment, which is declining in popularity.

Kenya’s gig economy: a precarious and exploitative work?

Many online workers are attracted to the gig economy because it accords them an independence that they would not have in formal employment. For instance, they can choose who to work for, set their own working hours and work remotely. Despite these advantages, online gig workers face many challenges, for example:

- Including stiff competition for online jobs.

- A lack of a stable income, which makes them ineligible for financial services such as loans or insurance.

- A high cost of doing business, since gig workers often have to cover the costs of their own equipment, transport and other overheads that would otherwise have been borne by an employer.

- A lack of job security, since their platform accounts can be suspended or deactivated without notice in the event of customer complaints.

- A lack of a safety net, such as health care benefits and pensions.

The majority of these challenges can be addressed through regulation to ensure socially just gig work. Unfortunately, while Kenya has labour laws that aim to protect workers, these laws are tailored to the formal employment sector. The International Labour Organization (ILO) acknowledges that regulating informal labour presents a challenge for most countries because existing laws are often incomplete, too vague, out of date, or unclear regarding the definitions of the players in the industry, thus creating loopholes for the exploitation of workers. The lack of an appropriate regulatory framework for informal online workers exposes them to high compliance costs due to multiple licensing demands. Similarly, they are vulnerable to harassment, unclear terms of recruitment, punitive dismissals and unfair work environments.

Shedding light on the livelihood on Kenya’s gig workers

Empirical evidence from a recent study of 314 online gig workers by the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society, in cooperation with the Digital Transformation Center Kenya of the Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), revealed weaknesses in the regulatory mechanisms for the online gig economy in Kenya.

It emerged that most 282 (89.8%) of the gig workers in Kenya consider the gig work as their primary source of income while 32 (10.2%) use it as a supplemental income generation avenue.

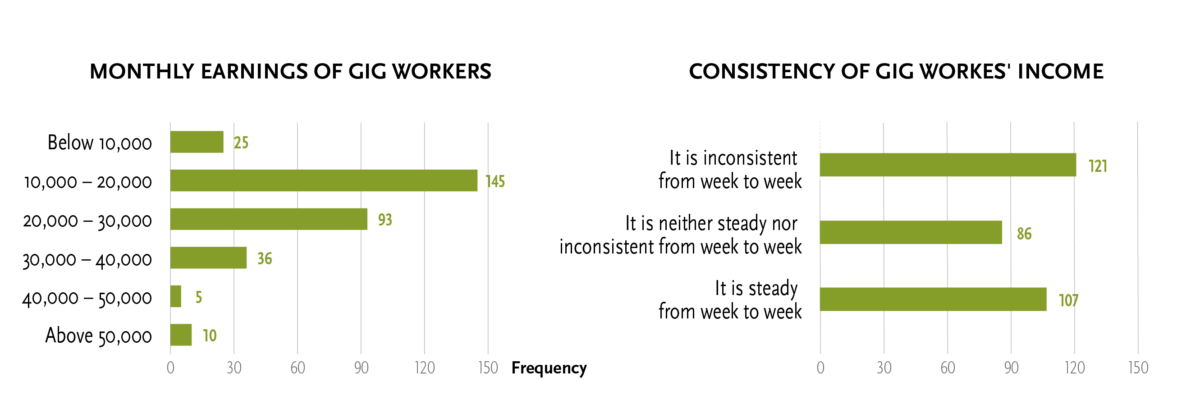

However, the majority of the gig workers earned low wages ranging between 10,000 and 30,000 Kenya Shillings monthly (80-240 EUR). Furthermore, most of the gig workers indicated that the income was inconsistent and varied from week to week.

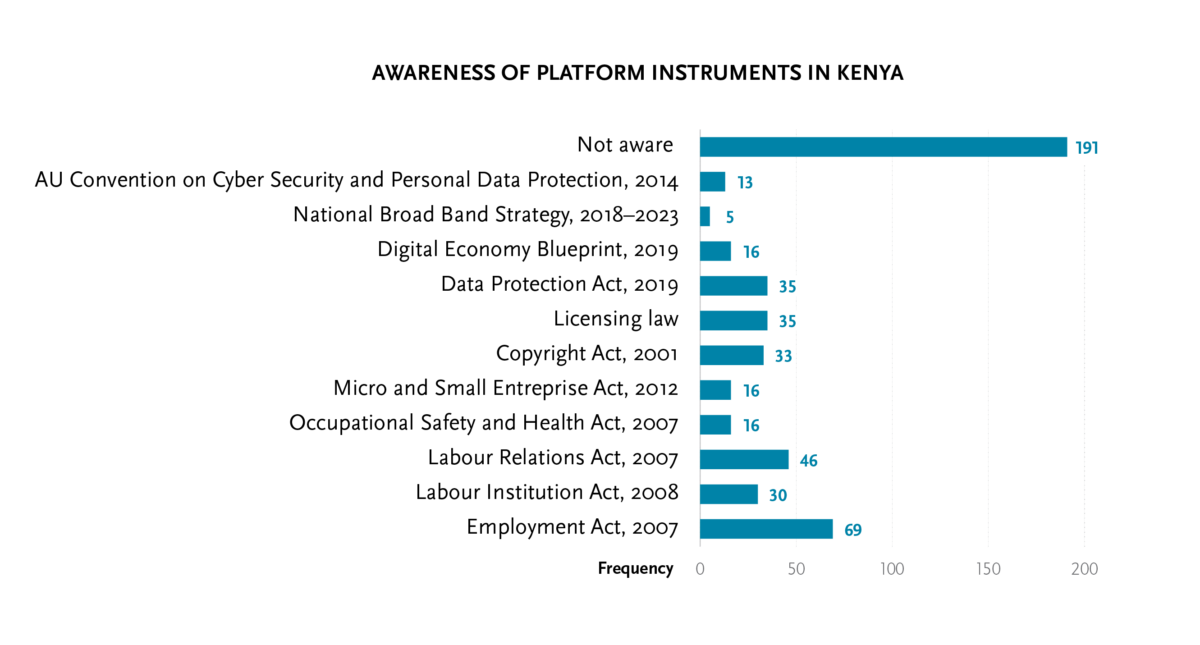

Although the majority (81.5%) of the respondents said that they have a contract with the platforms they worked on, 18.5% of the respondents had no contracts. Similarly, most (93.0%) of the respondents were aware of the terms and conditions of their engagement but 7.0% of them did not know their terms of engagement. Additionally, 13.0% of the respondents were not aware of any policies on the platforms they used. Importantly, most (60.8%) of the respondents were not aware of any regulations used to manage gig platforms in Kenya.

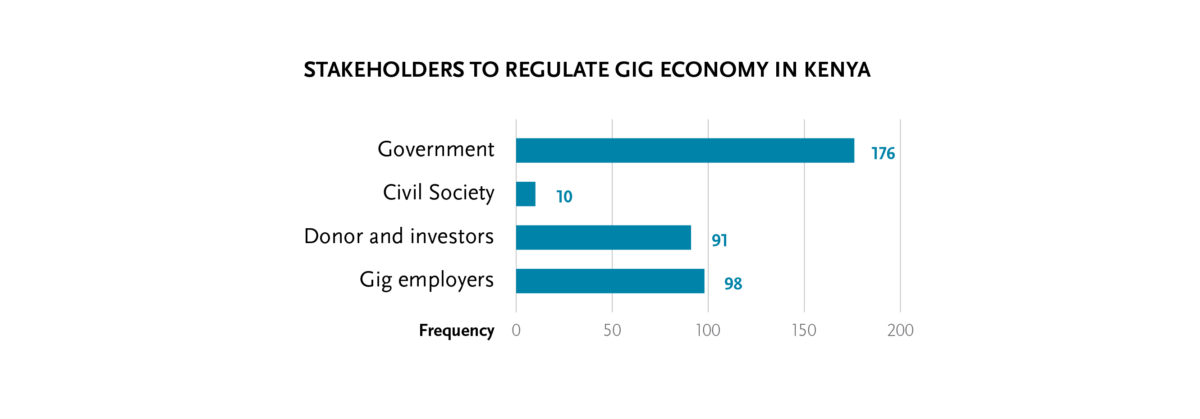

In terms of regulation, most of the respondents (56,0%) indicated that the Government of Kenya is best placed to regulate gig platforms with the support of the other stakeholders including donors and investors, civil society organisations, and the platform owners or employers. The findings of the study also revealed that most (50.3%) of the gig workers felt that the stakeholders did not support the gig economy. There was generally a low awareness of labour unions and welfare societies among online gig workers.

How to ensure justice and fairness in Kenya’s gig economy

These findings show that the Kenyan gig economy is controlled by platform owners who operate using a business model that is steeped in making profit. This model works to benefit the employer the most. For example, Uber drivers are monitored using GPS technology, but the drivers themselves cannot monitor their employer. Also, the platform dictates the terms of transactions for the worker. The gig platforms also allow customer ratings of employees rather than direct supervision by the employer. Furthermore, most of the gig workers’ employers have the capacity to set wages, which is influenced by factors like the number of gig workers on the platform, the rate of unemployment and work preferences. There is a need to regulate the platforms as a means of guaranteeing justice and worker welfare. Given that platform owners would naturally be interested in having a say in regulation, the other stakeholders should take the lead in fostering a regulatory regime that balances the needs of the online gig workers with the business interests of the platforms. The Government of Kenya should recognise gig work as employment and gig workers as employees whose rights need to be protected legally. Similarly, the Government of Kenya, in collaboration with the other stakeholders, should review, revise or update the legal and policy frameworks governing terms of employment, workers’ rights and welfare to include the interests of the burgeoning number of online gig workers in the country. Gig workers in Kenya should be sensitised to their rights as employees and should be encouraged to join unions that can lobby and advocate for their rights. Civil society organisations and unions should spearhead initiatives in this regard.

Steps towards a socially-just gig economy in Kenya

The Government of Kenya should also identify and implement strategies that diversify and promote gig work as an alternative income generation mechanism for both employed or unemployed citizens. Civil society organisations and unions alike should provide affordable or free legal advice or representation to gig workers whose rights are violated but who have no means of seeking legal redress. The judiciary of Kenya should create a section for gig workers under its Labour and Employment Division. This would strengthen the capacity of the judiciary to handle disputes emerging from gig work competently and expeditiously. Programmes for capacity building should expand their horizons to include mentorship, hand-holding and acceleration mechanisms to create and strengthen the practical skills needed by the gig sector.

Annotations

*The estimations were made during a multi-stakeholder dialogue event hosted by the HIIG and GiZ in Nairobi, Kenya on 9th November 2022.

About the study

The findings presented in this article are based on a study conducted by the authors as part of their research in the Sustainability, Entrepreneurship and Global Digital Transformation (SET) project in Kenya in 2022. It is going to be published in spring 2023.

The SET project is organised by HIIG in cooperation with the Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) . In Kenya and multiple other countries, HIIG supports the BMZ’s Digital Transformation Centers (DTCs) as a scientific partner and carries out exchange and research formats in partner countries.

About the authors:

Kutoma J. Wakunuma, PhD is an Associate Professor at the Research and Teaching School of Computer Science and Informatics at De Montfort University Leicester, United Kingdom

Tom Kwanya, PhD is a Professor for Knowledge Management School of Information and Communication Studies at the Technical University of Kenya Nairobi, Kenya

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Digital future of the workplace

Platform governance

Online echoes: the Tagesschau in Einfacher Sprache

How is the Tagesschau in Einfacher Sprache perceived? This analysis of Reddit comments reveals how the new simplified format news is discussed online.

Opportunities to combat loneliness: How care facilities are connecting neighborhoods

Can digital tools help combat loneliness in old age? Care facilities are rethinking their role as inclusive, connected places in the community.

Unwillingly naked: How deepfake pornography intensifies sexualised violence against women

Deepfake pornography uses AI to create fake nude images without consent, primarily targeting women. Learn how it amplifies inequality and what must change.