Making sense of our connected world

Identifying bias, taking responsibility: Critical perspectives on AI and data quality in higher education

The landscape of higher education is at a turning point: artificial intelligence is fundamentally transforming teaching, research and study. Language models such as ChatGPT and Claude are already being used in everyday university life, but this raises urgent questions. This article particularly focuses on the issue of bias in AI systems, explaining why universities must adopt a conscious and critical approach to this technology.

The higher education sector is undergoing a profound shift: the use of artificial intelligence (AI) — whether in the form of agents, automated decision-making systems (ADM systems) or generative AI (GenAI) is changing the way we teach, learn and conduct research. Although the use of AI in admissions processes remains controversial, large language models such as ChatGPT and Claude have long been part of academic life. These models support students and staff by helping them to write essays, structure complex research projects and prepare teaching materials. However, as appealing as these new possibilities may be, the questions they raise are all the more pressing. This article focuses on bias in and through AI systems, highlighting its particular relevance in a university context and explaining why deliberate, critical engagement with this technology is essential.

The paradox of apparent neutrality

Artificial intelligence is often hailed as a key technology of the future, driving innovation, efficiency and societal progress. However, its foundations lie in data, and data is never neutral. As algorithms learn from historical information, they inevitably reproduce social, cultural, and economic power relations. Rather than generating equitable solutions, many AI systems perpetuate existing inequalities and translate mechanisms of exclusion into code (Mosene, 2024).

By doing so, AI amplifies the discriminatory logic of the societies that produce it. Marginalised groups, including women, BIPoC, LGBTIQA+ individuals, people with disabilities and those in precarious socio-economic circumstances, are disproportionately affected. The underrepresentation of marginalised groups, together with their distorted or stereotypical portrayal, creates a spiral of disadvantage: biased data produce biased outputs, which then enter new datasets and shape future decisions. A wide range of scholarly analyses clearly demonstrate this development (Buolamwini & Gebru 2018; Benjamin 2019; Eubanks 2018; Noble 2018).

Another issue arises beyond training data: AI tools are not neutral technologies. Instead, they reflect the worldviews, values, and blind spots of the teams that develop them. These teams are predominantly located in the Global North and consist largely of white men. Consequently, marginalised perspectives and needs are systematically overlooked (D’Ignazio & Klein 2020; Buolamwini & Gebru 2018; Benjamin 2019; Eubanks 2018; Noble 2018).

Recent data from 2024 (Lazzaroni & Pal, 2024) shows that women currently make up only around 22% of the global AI workforce. In other words, approximately four out of every five people employed in AI are men. Even in regions known for promoting gender equality, the AI sector lags behind. Germany, for example, is a country that has reduced much of its broader gender inequality, yet it has one of the lowest proportions of women in AI-related roles in Europe, at just 20.3%.

The past as a predictor of the future

These systematic biases also have immediate implications for universities at several levels. The use of AI systems at an institutional level, for instance in admissions, assessment or academic advising, is a topic of increasing debate at German universities. However, any decision to deploy AI in such sensitive areas should not be taken lightly. Since these decisions concern access, achievement and equal opportunities, the debate must be informed, open-minded and attentive to potential negative consequences. If AI systems are used to analyse historical data, detect patterns and make predictions about the future, there is a substantial risk of circular reasoning, self-fulfilling prophecies and the continued exclusion of certain groups (Wilson & Caliskan, 2024).

France’s experience illustrates the risks: for years, an algorithm was used to allocate university places. It was later revealed that seemingly neutral criteria, such as place of residence, led to systematic disadvantage. Applicants from the wealthy central districts of Paris were admitted more frequently, whereas candidates from the banlieues (socially disadvantaged suburbs) faced significantly lower chances of admission, particularly to the country’s most prestigious universities (Martini et al., 2020). Rather than promoting fairness, the system exacerbated existing social inequalities.

Paradoxically, universities — institutions that pride themselves on critical thinking and societal innovation — deploy technologies that primarily reinforce existing patterns. For this reason, it is essential that, before implementing technical solutions, universities first address fundamental ethical questions: Which systems should we use, and what are the associated benefits and drawbacks? What understanding of fairness, accountability, and transparency should guide the use of AI in teaching and administration? What minimum standards must be met? How can we ensure that all students, staff, and researchers are included?

Concrete risks for teaching and research

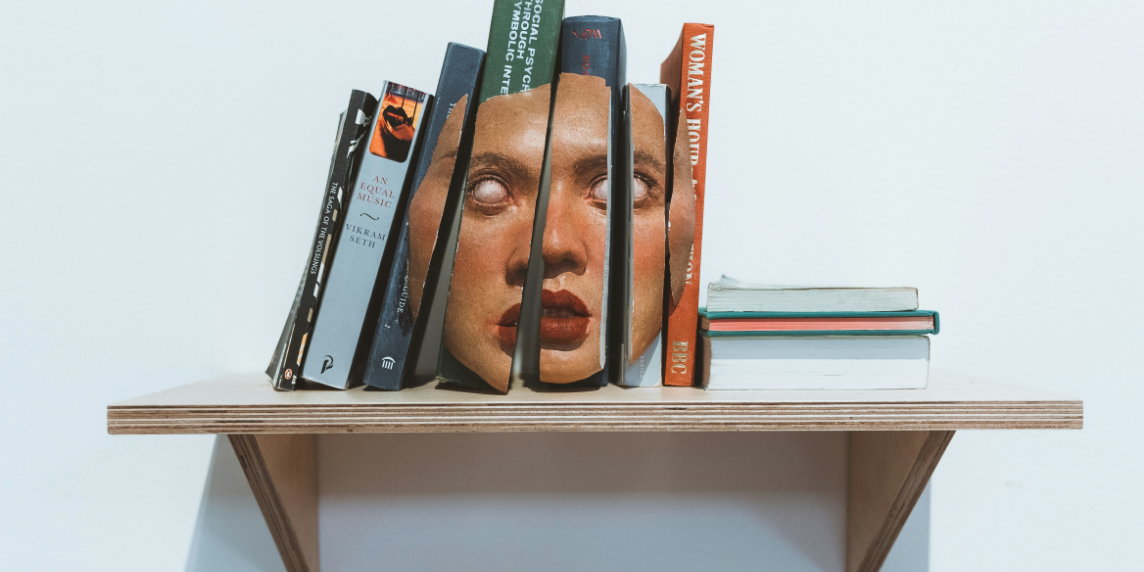

At an individual level, GenAI reproduces the biases embedded in its training data, transferring them directly into teaching, learning and research. Large language models (LLMs) are a particularly clear example of this: when students or researchers use LLMs to search for literature, these systems tend to prioritise the work of established authors — who are often male, white and based in the Global North (Algaba et al., 2024; He, 2025). By contrast, marginalised perspectives remain largely invisible (Elsafoury, 2025).

This imbalance is closely tied to the models’ training foundations: most are built on datasets that are dominated by English-language materials from the Global North. This results in outputs that reproduce a highly selective body of knowledge and entrench stereotypical assumptions. The consequences are evident: texts and images generated by large language models frequently contain sexist (UNESCO, 2024) or racist patterns (Nicoletti & Bass, 2023). For students, this means that their reasoning and learning processes may become distorted by these one-sided structures, resulting in blind spots that go unnoticed due to a lack of critical reflection.

The uncritical use of GenAI also risks undermining fundamental academic skills. If AI routinely provides arguments and analyses, individuals’ analytical abilities may erode. Skills such as identifying and evaluating primary sources and synthesising conclusions from diverse materials may likewise diminish through overreliance on AI (Gerlich, 2025). In this way, GenAI increasingly challenges the core principles of academic freedom and integrity.

If not used reflectively, AI risks becoming a force that reinforces existing inequalities in teaching and study. Rather than opening up new perspectives or fostering critical thinking, it may consolidate existing power structures and restrict the diversity of academic discourse. Consequently, it risks contributing to the entrenchment of exclusion rather than the democratisation of knowledge. This is precisely why universities must adopt a deliberate, critical and reflective approach to generative AI; otherwise, it threatens the very principles that define the university: openness, equal opportunity, and the cultivation of critical judgement.

Conclusion: Taking responsibility

For universities, using AI involves far more than simply introducing new technologies; it requires a considered approach. Transparent communication about opportunities, limitations and risks lies at the heart of this. Strengthening critical media literacy is essential so that staff, students and teaching personnel can develop a meaningful understanding of how AI works and where its boundaries lie.

It is equally important to include diverse — particularly marginalised — perspectives to ensure the implementation of AI tools is participatory and inclusive. Ethical guidelines should also be established to define clear rules for the responsible use of AI.

This includes:

- There should be transparent communication about the opportunities, limits and risks of AI in higher education.

- Developing critical media and methodological competencies among students, staff and teaching personnel to enable them to thoughtfully assess AI content and usage.

- Inclusion of diverse, particularly marginalised, perspectives and participatory processes in the deployment and implementation of AI tools.

- The establishment of ethical guidelines that set out clear rules for the responsible use of AI.

- There should be continuous reflection on the societal consequences of AI, such as bias, exclusion and systemic distortions.

Generative AI will transform higher education in lasting ways — this development is unstoppable. Therefore, the decisive question is not whether AI will be used, but how. Universities should strive to become pioneers in the critical and reflective use of AI. This requires an awareness of the limitations of these technologies, particularly with regard to biases, exclusions, and systemic distortions. Equally vital is cultivating methodological skills that enable users to critically and knowledgeably evaluate AI-generated content.

Alongside this, there must be ongoing ethical reflection on the societal implications of AI. Only then can universities fulfil their responsibility as educational institutions while harnessing the potential of AI and GenAI without ignoring the associated risks. The future of higher education depends on our ability to critically reflect on technology rather than placing blind trust in it.

This article was first published in German on 6 October 2025 by the Hochschulforum Digitalisierung.

Authors

Katharina Mosene is a political scientist, co-project coordinator, and research associate in the Human in the Loop project at the HIIG. At the Leibniz Institute for Media Research │ Hans-Bredow-Institut, she is also responsible for strategic research collaborations and event partnerships. In addition, she is a founding member of netzforma* e.V., an association for feminist internet policy.

Johanna Leifeld has been working at the CHE Centre for Higher Education since 2022 as a project manager for the Hochschulforum Digitalisierung. She is involved in strategy development and is responsible for its peer-to-peer consulting programme for academic departments. She is also part of the team behind the University:Future Festival, the largest German-language event on innovation in higher education.

References

Algaba, A., Mazijn, C., Holst, V. T., Tori, F. J., Wenmackers, S., & Ginis, V. (2024). Large Language Models Reflect Human Citation Patterns with a Heightened Citation Bias. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.15739

Benjamin, R. (2019): Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the new Jim Code. Cambridge, UK. Polity Press. https://doi.org/10.23987/sts.102639

Buolamwini, Joy/Gebru, Timnit (2018): Gender Shades. https://www.media.mit.edu/projects/gender-shades/overview/

D’Ignazio, C. & Klein, L. (2020). Data Feminism. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11805.001.0001

Elsafoury, F., & Hartmann, D. (2025). Out of Sight Out of Mind: Measuring Bias in Language Models Against Overlooked Marginalized Groups in Regional Contexts. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.12767

Eubanks, Virginia (2018): Automating Inequality – How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. St. Martin’s Press. https://doi.org/10.5204/lthj.v1i0.1386

Gerlich, M. (2025). AI Tools in Society: Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking. Societies, 15(1), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15010006

He, J. (2025). Who Gets Cited? Gender- and Majority-Bias in LLM-Driven Reference Selection. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.02740

Lazzaroni, R.M. & Pal, S. (2024) AI’s Missing Link: The Gender Gap in the Talent Pool. Interface EU. https://www.interface-eu.org/publications/ai-gender-gap

Martini, M., Botta, J., Nink, D., & Kolain, M. (2020). Automatisch erlaubt? Fünf Anwendungsfälle algorithmischer Systeme auf dem juristischen Prüfstand. Bertelsmann Stiftung. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/publikationen/publikation/did/automatisch-erlaubt

Mosene, K. (2024) Ein Schritt vor, zwei zurück: Warum Künstliche Intelligenz derzeit vor allem die Vergangenheit vorhersagt. Digital Society Blog (HIIG). https://www.hiig.de/warum-ki-derzeit-vor-allem-vergangenheit-vorhersagt/

Nicoletti, L., & Bass, D. (2023): Humans Are Biased. Generative AI Is Even Worse. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2023-generative-ai-bias/

Noble, S. U. (2018): Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479833641.001.0001

UNESCO, IRCAI (2024). Challenging systematic prejudices: an Investigation into Gender Bias in Large Language Models. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000388971

Wilson, K., & Caliskan, A. (2024): Gender, Race, and Intersectional Bias in Resume Screening via Language Model Retrieval. Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 7(1), 1578-1590. https://doi.org/10.1609/aies.v7i1.31748

This post represents the view of the author and does not necessarily represent the view of the institute itself. For more information about the topics of these articles and associated research projects, please contact info@hiig.de.

You will receive our latest blog articles once a month in a newsletter.

Artificial intelligence and society

Open higher education

The Human in the Loop in automated credit lending – Human expertise for greater fairness

How fair is automated credit lending? Where is human expertise essential?

Impactful by design: For digital entrepreneurs driven to create positive societal impact

How impact entrepreneurs can shape digital innovation to build technologies that create meaningful and lasting societal change.

Who spreads disinformation, where, for what purpose, and to what extent?

How much disinformation do German politicians and parties actually spread? On which platforms and to what ends? Two new studies provide systematic answers.